Thyroid hormones explained as simply as possible…

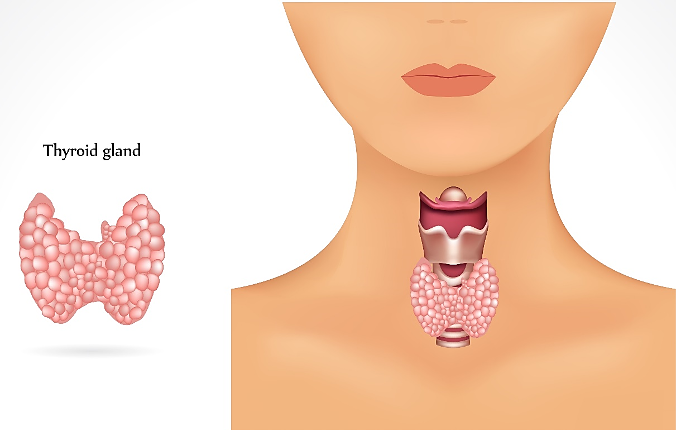

The thyroid gland is a butterfly-shaped organ about the size of a plum. It sits 1/2 inch under the skin at the front of the neck, just below the Adam’s apple. The thyroid gland is responsible for producing hormones that regulate metabolism, body temperature, childhood growth and development, the menstrual cycle, and functions of critical organs such as the brain, heart, GI tract, muscles, and nerves.

Thyroid Hormones

Thyroid explained

Thyroid Hormone Balance

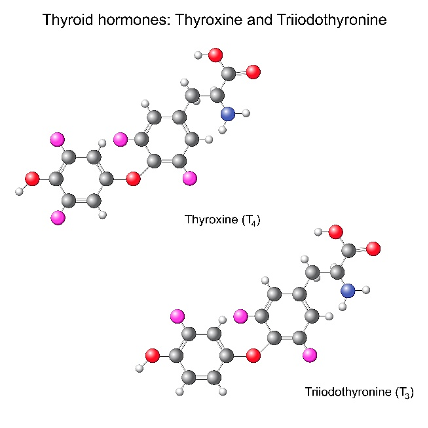

T4 and T3 are released by the thyroid when stimulated by the pituitary hormone Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH). In turn, TSH is released by the pituitary into the circulation when pituitary cells are stimulated by the hypothalamus (brain) hormone TSH Releasing Hormone (TRH). After TRH stimulates the pituitary to release TSH, which stimulates the thyroid to release T4 and T3, the T3 circulating in the bloodstream, in turn, acts on the hypothalamus to turn-off release of TRH, and again on the pituitary to block the release of TSH.

This process, the hormone itself, turns off the hormones that stimulate it, known as “negative feedback” regulation. Negative feedback ensures that T4 and T3 levels never get too high or too low in your blood. When T4/T3 levels are high, they cause negative feedback to turn-off TRH and TSH, resulting in less new T4/T3 by the thyroid. When T4/T3 levels are low, there is a lack of negative feedback, TRH and TSH are now upregulated, and the thyroid gland produces new T4/T3.

So, TSH, TRH, T4/T3 are in a continuous balance that works beautifully in most cases. Of course, all these relationships break down when a health problem affects the hypothalamus, pituitary, or thyroid gland itself. One benefit of this natural balancing act is that we can measure TSH (the “middle” hormone in the sequence) as a way of figuring out if the thyroid hormone is being produced in too little or too much quantity.

TSH increases if the thyroid is unwell and cannot make enough thyroid hormone, and TSH decreases if the thyroid is making too much thyroid hormone (which can happen in Graves disease or other thyroid conditions). TSH can also decrease in someone with an inactive thyroid (hypothyroidism) who receives too much thyroid hormone replacement medication. So, in summary, even though TSH levels go “opposite” of the direction of thyroid hormone levels, TSH provides a good basic “read-out” of the total thyroid hormone balance for most people: TSH too high = too little thyroid hormone around; and TSH too low = too much thyroid hormone around.

What are good thyroid numbers?

There are well-established normal ranges for TSH, T4, and T3… but, if only it were so simple to say, “Your numbers are in the normal range, so everything is great!” Good medical practice is never that simple. We will start by considering the effects of the binding of levothyroxine (T4) and liothyronine (T3) to proteins. T4 and T3 each circulate almost entirely bound to a blood protein called “thyroglobulin” and, to a lesser extent, bound to a few other proteins in the blood. We call these “carrier proteins.” In fact, only 0.03% of T4, and only 0.3% of T3 in the blood are circulating “free,” meaning floating in the blood is not bound to any carrier proteins. At any given time, less than half-a-percent (0.5%) of the entire amount of your thyroid hormone (T4+T3) in your blood is free and can interact in any meaningful way with other tissues. Unfortunately, the numbers above for % binding are “population averages,” and your personal amount of T4/T3 bound to your carrier proteins probably differs from other people.

This person-to-person variation occurs for many reasons, including minor genetic differences (mutations) or other modifications in the carrier proteins and other blood factors that influence how strongly your hormones bind to the carrier proteins. For this reason, it is critical that your doctor measures “Free T4” and “Free T3” levels instead of the “total” hormone levels. This is particularly true for T3, which, because it is less strongly bound to carrier proteins (10-times more weakly bound than T4), it is more likely to get “bumped-off” its carrier proteins and tends to vary more from person to person. Measurement of total T3 is practically useless in most clinical settings and should not be done. Most Endocrinologists will prefer to measure Free T3 when a reliable test is available at the local laboratories.

TSH normal ranges are also “population averages,” and what is normal and abnormal is a common contention area among some medical providers who do not understand that fact and people who do. The normal range of TSH spans roughly from 0.5 to 5 mcIU/mL—that is a 10-fold range from the lowest level considered “normal” to the highest level considered “normal.” Keep in mind that TSH goes up when there is not enough thyroid hormone around and goes down when there is too much thyroid hormone. High or low TSH (even when Free T4 or Free T3 are in the normal range) indicates too little or too much thyroid hormone, respectively. If you are taking a thyroid hormone, you either entirely lack a functioning thyroid gland (you make no thyroid hormone) or make too much thyroid hormone. It does not take a Ph.D. in physiology or biochemistry to understand that some people may feel better at the lower end of the TSH normal range (e.g., approximately 0.5 to 2 mcIU/mL).

In comparison, some people may feel better at the higher end of the TSH normal range (e.g., approximately 2 to 5 mcIU/mL). Most Endocrinologists are willing to work with you to address your symptoms and adjust your thyroid hormone doses enough to move you a bit more toward one end or the other of the “normal” range, so long as you remain in the normal range. These sorts of minor adjustments can have an important effect on symptoms related to your thyroid balance. It is important to stay in the normal range in nearly all cases since there are definitely unwanted complications that can and will arise if your TSH remains too low or too high for a prolonged period of time. Adjusting thyroid medications to the point that your TSH falls outside of the normal range is a situation in which, while still an issue of the “population average,” carries enough negative consequences that it should be avoided.

Thyroid test

Check your Thyroid

What is the best type of thyroid medicine?

In general, it is a good idea to start by taking just levothyroxine (T4) if your thyroid does not make enough hormones (i.e., for hypothyroidism). Levothyroxine is an inactive hormone and must be converted into active T3 to affect other tissues in your body. Most organs other than the brain are good at converting T4 to T3 and do so in such a way that you get just the right amount of both. 85% of people feel fine on levothyroxine (T4), and since it is easier to manage just that one medication, with fewer chances of side effects, just T4 alone is preferred by most Endocrinologists and people. However, some people are poor “T3 converters”, even when they are otherwise healthy: these people will have lower than usual levels of T3 in their blood and complain of symptoms like hypothyroidism. Sometimes these people feel better when adding a small amount of T3 (liothyronine, brand Cytomel) to their regimen.

Also, people who have had their thyroid surgically removed due to thyroid cancer or other problems like thyroid nodules or Graves disease—the term used for these people is “a thyroidal”— often feel the effects of losing the small amount of T3 their thyroid would normally have made every day. As a result, they often have hypothyroidism symptoms even when their thyroid hormone levels are in the normal ranges (including normal T3 levels). In these cases, adding a small amount of T3 (as the medication, liothyronine) to the levothyroxine (T4), they are taking every day can improve their symptoms.

This is also the case for many people who have traditional hypothyroidism due to thyroid failure (such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis) and who now require a “complete body replacement dose” of thyroid hormone. These are typically people who require 100 mcg or more per day of levothyroxine (T4) to keep their thyroid hormone and TSH levels normal. For these people, adding some T3 (liothyronine) to their daily regimen can also help with symptoms. T3 (liothyronine) can be added as a second pill taken every day (brand name is Cytomel), or by switching people to pig thyroid extract (brand names are NP thyroid, Armour thyroid, and WP thyroid).

People should be careful when choosing the pig extracts since the amount of T3 in pig thyroid is about 3 times the amount in human thyroid, and sometimes this will cause hyperthyroidism symptoms. In general, it should also be noted that T3 (liothyronine) is 4-times more potent that levothyroxine, and so if your Endocrinologist needs to add T3, it is usually necessary to drop your levothyroxine dose quite a bit to accommodate the T3 since it is so much more potent. Without dropping the levothyroxine dose, many people will develop hyperthyroidism. We call this “iatrogenic” hyperthyroidism—which means medication-induced—when it occurs due to getting too much medication. Iatrogenic hyperthyroidism, just like naturally occurring hyperthyroidism, can lead to heart and muscle weakness and permanent bone damage (osteopenia, osteoporosis, hip, spine fractures, etc.).

Thyroid conditions

Thyroid hormones and your body weight

Thyroid hormones regulate the rate of metabolism in cells throughout your body, and as a result, your body temperature too, since how quickly your cells “burn energy” determines how much heat they produce. Burning energy also literally means “burning calories”. Many people (and nearly every website trying to sell you something) think this means that thyroid hormones play a critical role in regulating your body weight. Unfortunately, the thyroid only has a small impact on your ability to gain weight or lose weight. There are some exceptions of course, and so the role of your thyroid in weight management should not be entirely ignored.

Even so, do not count on the idea that adjusting your thyroid medication, or treating mild hypothyroidism, will somehow be a critical fix for being overweight. If only it were that easy! If anyone tells you something different, then they are probably trying to sell you a supplement, a diet, a book, or a membership, or just trying to get you to hit their web pages repeatedly so they get more web advertising dollars. Inform yourself and use the internet as a tool, but learn to be a savvy internet medical investigator, especially when it comes to thyroid. There is a great deal of false information out there intended to hook you and reel you in!

Regulation of heart, brain, nerves, and muscle by thyroid hormones

Thyroid hormones also regulate how quickly electrical signals move through organs and tissues such as your heart, muscles, and nerves. In general, the more thyroid hormone around, the more quickly electrical signals travel, and the less thyroid hormone around, the more slowly electrical signals travel. These electrical effects show up in several ways.

For instance, in people with low thyroid hormone levels, the heart beats more slowly, the brain functions a bit less sharply, leading to depression and brain-fog, muscles are slow to engage, nerve reflexes are “dull,” and nerves controlling the GI tract move food along too slowly (e.g., causing bloating and constipation).

In contrast, in people with high thyroid hormone levels, the heart beats quickly and may even skip beats or develop irregular rhythms, the brain is amped-up resulting in anxiety, irritability, and insomnia, muscles become jittery and overstimulated and start to deteriorate, nerve reflexes are exaggerated, and nerves controlling the GI tract move food along too quickly (e.g., causing overly frequent bowel movements or diarrhea).

Thyroid regulation

Thyroid Pain

What are the types of thyroid disorders?

The two types of thyroid disorders related to the gland's activity (hormone production) are hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Hyperthyroidism is the overproduction of the hormones thyroxine (T4) triiodothyronine (T3) by the thyroid gland. When the body overproduces thyroxine, it has the effect of unnecessarily speeding up your metabolism and nerve conduction, causing an irregular heartbeat, fatigue, anxiousness, insomnia, and muscle weakness. Too much T4/T3 can also cause permanent injury to your bones (osteopenia or osteoporosis), resulting in hip and spine fractures at an early age. Hypothyroidism affects 1 in 20 people in the U.S. and is far more common than hyperthyroidism (about 1 in 100 people).

An underactive thyroid gland causes hypothyroidism. With hypothyroidism, the thyroid gland cannot produce the necessary hormones for your body. An overactive thyroid gland causes hyperthyroidism. This is normally a very carefully tuned process that ensures your thyroid gland only makes the amount of T4/T3 you need at any given time. In hyperthyroidism, the thyroid gland continues to make T4/T3, sometimes in large quantities, even when you do not need more thyroid hormone.

The three other main types of thyroid disorders are (i) thyroid nodules, for which 90% are benign, but they can cause pain, swallowing problems, and changes in your voice; (ii) thyroid cancer (makes up 10% of thyroid nodules that are not benign)—even though it tends to be very slow-growing, we worry about thyroid cancer and try to remove it immediately, because it can spread to your lungs and bones, and rarely some other organs making it much harder to treat; (iii) thyroid inflammation (thyroiditis)—this problem affects women 4-times more frequently than men; in many cases, it occurs in the months after pregnancy and is painless, but even so, it can cause many symptoms of hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism, and sometimes gets mistaken for post-partum depression!

Other thyroid-related symptoms you may experience.

Both too much or too little thyroid hormone can cause irregularities in the menstrual cycle and affect women's fertility. Both too much or too little thyroid hormone affect hair, skin, and nail health, and both conditions can cause hair loss. However, be aware that iron deficiency is a common, non-thyroid-related cause of hair loss in women. Some people can develop fibromyalgia-type symptoms with too little thyroid hormone, including chronic, low-grade muscle and joint aches and pains.

Thyroid - losing hair

Thyroid

Too little T4 and T3 (hypothyroidism):

- Depression

- Tiredness and fatigue

- Difficulty concentrating

- Dry skin

- Brittle nails

- Hair loss, eyebrow thinning

- Sensitivity to cold temperature

- Joint and muscle pain

- Frequent, heavy periods

Too much T4 and T3 (hyperthyroidism):

- Anxiety

- Irritability or moodiness

- Insomnia

- Nervousness, hyperactivity

- Sweating or sensitivity to high temperatures

- Hair loss

- Hand trembling (shaking)

- Missed or light menstrual periods

Should I take thyroid medicine if I feel like I have a thyroid problem, but my numbers are normal?

In general, this is probably not a good idea. People often imagine that thyroid hormone (and other hormones like estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone) are sort of like “vitamins.” If you are feeling “off,” they think, “Just take some of these hormones to get things back on track; give yourself a little boost.” However, hormones are not anything like vitamins. Most vitamins are not toxic when you take a bit more than your body may need. In contrast, hormones can have serious or deadly effects if you take them when you do not need them.

Taking thyroid medication if you do not need it can cause dangerous heart arrhythmias that result in sudden cardiac death, puts you at risk for serious heart and muscle problems, and permanently damages your bones (osteopenia, osteoporosis, fractures of the hip or spine, etc.). There is possibly one exception to this rule, however. Some people with thyroid hormone levels in the normal range may have Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (Hashimoto’s disease), chronic autoimmune destruction of the thyroid gland.

Hashimoto’s disease is defined in part by detecting antibodies in the blood that targets the thyroid gland. Though not currently recommended by the American Thyroid Association (or AACE or Endocrine Society), it could nevertheless be reasonable and safe to give some people with Hashimoto’s disease a small thyroid hormone dose, but only if their TSH is elevated at the upper end of the normal range. Remember: TSH spans a 10-fold range from roughly 0.5 to 5 mcIU/mL), and your TSH level goes opposite the amount of thyroid hormone your gland is making.

So a TSH that has climbed to the upper end of the normal range could indicate you are making less thyroid hormone than your body would otherwise “prefer” to get if you did not have chronic ongoing autoimmune inflammation of your thyroid gland due to Hashimoto’s disease. By giving a small thyroid hormone dose, TSH would return closer to the mid-range of normal, and your symptoms might improve in that setting.

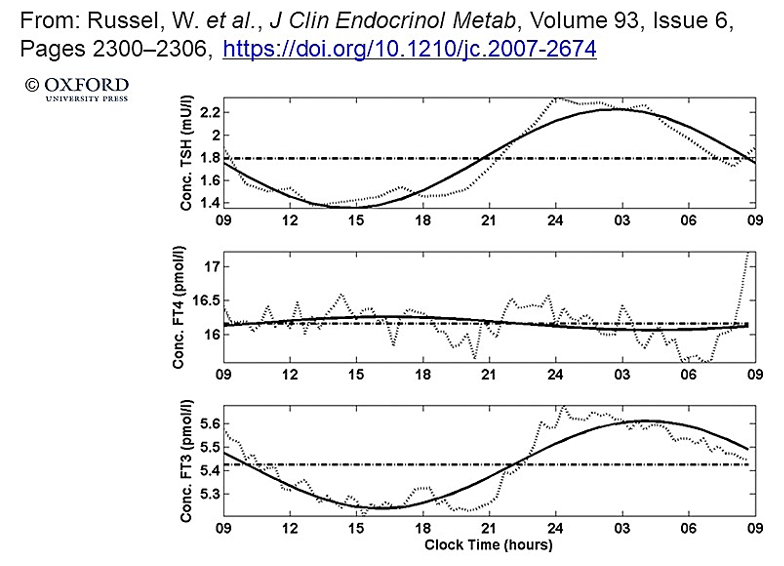

It would be important to not make decisions in this setting based on just one TSH measurement since TSH values (and Free T3) can fluctuate on average up to 30% on an hour-by-hour basis*, even with a completely healthy thyroid gland.

Note that this rationale is highly controversial, and most Endocrinologists do not ascribe to it. Even so, it is likely that there are some people with Hashimoto’s disease and high-normal TSH with symptoms of hypothyroidism that might feel better with a small dose of thyroid hormone. More research in this area is clearly needed.

Regulation of heart, brain, nerves, and muscle by thyroid hormones

In most cases, the answer is no. See work by Dr. Russel and colleagues above. These are graphs of TSH, Free T4, and Free T3 taken from the averages of 33 healthy people who had their blood measured every hour through a normal day in their lives. Look at the top and bottom graphs. The values of hormones are on the side (Y) axis, and the time of day in military format is on the bottom (X) axis. As you can see, most people exhibit a daily rhythm to their TSH and Free T3 levels, where they both hormones run highest in the early morning hours (peak at 3:00 AM) before waking, and lowest in the mid-afternoon (bottom-point 4:00 PM). The total average range of fluctuation is about 40% throughout the day.

Free T4 does not change much throughout the day. This all means that if your TSH climbs up or down by about 40% from where it had been previously, it most likely is just due to hourly “diurnal” variation and does not necessarily reflect a change in thyroid function for you. So, for people with normal thyroid medication, a change of TSH from 2.0 to 2.4 mcIU/mL or 0.9 to 1.2 mcIU/mL or even 3.0 to 1.9 mcIU/mL probably does not represent a medically important change in TSH. On the other hand, changes from 0.8 to 3 mcIU/mL or 2.5 to 1.2 mcIU/mL probably represent significant changes that should be investigated.

For people taking thyroid medication, similar variation from hour to hour can be seen depending on the type of thyroid medication they are taking, when they took their medication when they last ate, and what foods they last ate. One exception to this rule is people who have no thyroid gland due to surgery to remove their gland (thyroidectomy) for thyroid cancer. Endocrinologists often have given a bit of “extra” thyroid hormone to these people to “suppress” their TSH levels (i.e., keep them low) because TSH is a growth factor for thyroid cancer. Because TSH is not able to cycle in these people, their levels stay very stable and low on an hour-to-hour and day-to-day basis. Even small 0.1 to 0.2 mcIU/mL changes in thyroid hormone levels can be significant in these people and merit dose adjustment or further evaluation.

Thyroid chart

Thyroid Nodules & Biopsies

Thyroid pain

Should I worry about thyroid nodules?

Ninety percent (90%) of thyroid nodules are non-cancerous (benign). If you can feel a nodule growing at the lower base of your neck, it is probably a good idea to see an endocrinologist specializing in thyroid problems. Even though it is still likely to be benign, you can easily feel a nodule with a slightly higher risk of cancer than one that is found incidentally (on accident by imaging studies done for other reasons).

At Diabetes and Endocrine Treatment Specialists, we will typically see you the same day you call for this problem, so you do not have to worry about it for weeks, and we will do an ultrasound in our office at that first visit to get a better idea of what is going on. With ultrasound, it is often possible to conclude with good certainty whether or not a nodule is likely to be cancerous.

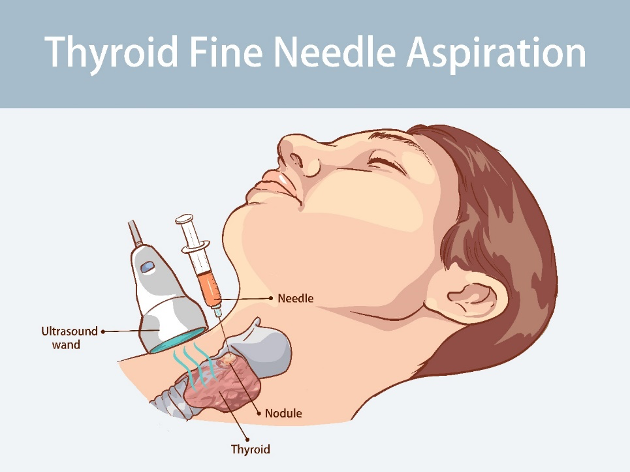

Still, if there is any question, we will perform an “ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration” (FNA) procedure. For the FNA, a very thin needle is used to collect a small sample of cells from your thyroid nodule to be examined. At Diabetes and Endocrine Treatment Specialists, we are among the leading experts in the Intermountain West regarding thyroid nodules and thyroid cancer. We perform several ultrasound-guided thyroid biopsies onsite in our clinic every day, hundreds per year. We also work with a panel of top-notch thyroid and neck surgeons throughout Utah, and so in the unlikely event you need surgery, we have you covered.

Thyroid Goiter

Do I need surgery for my thyroid nodule?

The short answer is usually not, but here are the potential situations where you might need surgery to deal with one or more thyroid nodules.

- An ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy shows one or more of your nodules is definitely thyroid cancer.

- Ultrasound-guided FNA biopsy shows one or more of your nodules is SUSPICIOUS for cancer (discussed more in a separate section).

- The thyroid nodule(s) are causing you to have swallowing problems.

- The thyroid nodule(s) are pushing on important structures in your neck like your trachea (windpipe), making it hard to breathe. Often, the breathing symptoms are noticed more when you turn your head or change your neck's position in certain ways.

- The thyroid nodule(s) are affecting your voice, causing problems with your speech.

- The thyroid nodules(s) are pushing on the jugular vein causing your face to swell and flush (turn red). The flushing sensation is often made worse by raising your arms over your head or turning your head/neck to one side or the other.

- The thyroid nodule(s) are pushing on your common carotid artery, causing dizziness, vision changes

Thyroid Fine Needle Aspiration

What is a thyroid biopsy? How are decisions for surgery made based on a thyroid biopsy?

A thyroid biopsy is a way of obtaining tissue from the thyroid without resorting to surgery. The most common way to biopsy the thyroid is to place a needle into the area of the thyroid of interest (usually into a thyroid nodule), using an ultrasound probe to guide the needle to its destination. The needle is usually very thin (or “fine”), and so the procedure is called an “ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy.”

When the needle is inserted into the thyroid, it is usually wiggled up and down several times, and a vacuum is applied by pulling back on the syringe. This helps tissue in the thyroid get sucked up or “aspirated” into the needle. The aspirated thyroid tissue, which looks like a thick liquid, is then ejected from the needle and smeared in slides or placed into a preservative tube. The samples are then sent to a pathology doctor known as a “cytologist,” who can stain the slides and examine the tissue in the jar with a microscope to see if there are signs of cancer.

What results can you get from a thyroid biopsy?

There are a handful of possibilities listed below. Your biopsy could show:

- Definitely benign—no signs whatsoever of cancer.

- Definitely, cancer—has one or more tell-tale signs that indicate thyroid cancer is definitely present.

- Atypia of undetermined significance (AUS)—there are abnormal features present, but whether or not they indicate, the cytologist cannot determine cancer.

- Suspicious for thyroid cancer—findings highly suggestive of thyroid cancer are present, but not enough to say there is cancer. Even so, with this diagnosis, there is up to a 40% chance that cancer really is present.

- Indeterminate for follicular thyroid cancer—follicular thyroid cancer is a type of cancer that cannot be diagnosed based solely on the tissue obtained from a thyroid biopsy. The sample can show all the features of follicular thyroid cancer. Still, until the thyroid is surgically removed, cut up, and further examined in more detail, it is impossible to know for sure. In this situation, the biopsy finding is called “indeterminate” for follicular thyroid cancer. Indeterminate literally means “we cannot really determine for sure yet whether it is or is not cancer.”

- Hürthle cell neoplasm—this category is similar to the “Indeterminate for follicular cancer” category above, in that a definite diagnosis of cancer or benign nodule cannot be made until the thyroid is surgically removed, cut up, and further examined under a microscope.

“Indeterminate” thyroid biopsy readings can be sorted out using new gene expression testing technology.

Until recently, if the cytologist reported the thyroid biopsy as “indeterminate for follicular thyroid cancer” or a “Hürthle cell neoplasm,” surgery was usually recommended to remove the lobe abnormal findings to examine it further to see whether or not thyroid cancer was really present. Depending on the level of suspicion for thyroid cancer, a thyroid lobectomy might also be recommended for a biopsy reported as “atypia of undetermined significance.” Since together, these types of biopsy findings make up about 20% of all biopsies, this approach led to many unnecessary surgeries, unnecessary because 60-70% of the lobes that removed were found to have no cancer in them.

Over the past decade, it has become routine to take a small portion (a few droplets) of the thyroid biopsy material and place it into a tube that can be sent for testing for abnormal genes (DNA sequences) in the thyroid tissue. If the cytologist reports the biopsy as “indeterminate,” then the material in the tube can be sent for this further testing, which usually provides enough information to determine with a high degree of confidence whether surgery is necessary. The ability to run this type of “gene expression classifier test” has practically eliminated unnecessary thyroid lobectomy surgeries in recent years. When we perform thyroid biopsies at Diabetes and Endocrine Treatment Specialists, we always prepare and set aside a separate tube for gene expression classifier testing, just in case the cytologist ends up reporting the biopsy as indeterminate.

Thyroid biopsy

Thyroid Cancer

Thyroid Cancer

Is thyroid cancer deadly?

In short: Yes, thyroid cancer can be deadly. A “5-year survival rate” tells you what percentage of people live at least 5 years after the cancer is found.

Overall, the 5-year survival rate for thyroid cancer is >98%, which is excellent compared with other types of cancer. And if you make it 10 years after diagnosis and treatment of thyroid cancer without it coming back, then there is much less likely it will give you problems in the future, and your survival rate rises to practically 100% for the rest of your life.

However, everyone should be aware that individual survival rates depend on many factors, including your age when diagnosed, gender, family history, a specific type of thyroid cancer, and whether it has already invaded tissues around in the neck or spread to other organs.

What happens to your body when you have thyroid cancer?

In the early stages of thyroid cancer, you may not show any symptoms. However, over time, you may have difficulty swallowing or breathing, develop a hoarse voice, get pain in the front of your neck near or below your Adam’s apple, or feel or see a lump or swelling in your neck.

By the time the more common form of thyroid cancer (Papillary thyroid cancer) is diagnosed, about 50% of people already have some small, microscopic amounts of it that has moved to the lymph nodes in their neck. For some cancers, any lymph node involvement is a very worrisome sign, but for thyroid cancer, these small amounts of cancer in the neck lymph nodes don’t seem to have much effect on long term outcomes.

Thyroid cancer seems to like to “set-up shop” in the neck lymph nodes and does not have a strong propensity to leave and go elsewhere. However, in some cases, if thyroid cancer goes too long without being diagnosed and/or treated, it can move (metastasize) from you neck to your lungs, bones, or other organs, where it can invade and cause many more problems, and even be life-threatening.

Thyroid cancer that spreads to other organs can be more difficult to treat. Even after spreading to other organs, oral treatment with radioactive iodine (131I) to target the thyroid cells that have spread throughout your body can be highly effective, and even cure the cancer, without damaging other cell or tissues.

As a result radioactive iodine is much less toxic than chemotherapy and acts sort of like a “silver bullet” to target just the cancer cells and leave everything else untouched. When oral treatment with radioactive iodine fails, there are now some newer classes of medications that can control metastatic thyroid cancer and keep it from further worsening.

What are the warning signs of thyroid cancer?

Thyroid cancer may not show any signs early in the disease. However, some symptoms may include: a lump or swelling that can be felt or seen at the base of your neck, trouble swallowing, changes to your voice, swollen lymph nodes, or pain in the front of you neck (usually just below the Adam’s apple).

What is the main cause of thyroid cancer?

We know a lot about what causes thyroid cancer at the level of genes and molecules that regulate the growth and behavior of cells in your thyroid gland. In some cases, you inherit an abnormal gene (mutation) from your parents, and this is what predetermines cancer for you. For most families with multiple members that develop thyroid cancer, we can identify one or several genes that are the cause.

These genes get passed down through the family in relatively predictable ways. However, most people with thyroid cancer do not have other affected family members, and in this case, we think that some genes in the thyroid gland that were previously normal at birth may have become damaged and are functioning abnormally due to aging and exposure to other factors.

One example of these factors is medical radiation. Note: we are NOT talking here about routine medical X-rays, CT scans, etc., but rather the sort of radiation therapy someone might get for treatment of other cancers like a lymphoma in the soft tissues of the neck or a bone cancer in the spine of the neck.

For this reason, people who have needed medical radiation to the head and neck for other cancers are often monitored with thyroid ultrasound every year to make sure there are no signs of cancer appearing over time. We are also increasingly recognizing that certain chemicals in the environment might cause thyroid cancer, including certain pesticides (organochlorides), phthalates and bisphenol compounds.

The latter two types of chemicals are by-products of the plastics industry, and nearly everyone has detectable levels of these in their blood and body tissues. They are even present at fairly high levels in breast milk! Since the dawn of the plastics industry in the 1930s, these chemical have become major environmental contaminants stretching to every single corner of the planet. Sadly, we are literally “swimming” in these chemicals and there is no way to clean them up.

So what can you do to avoid these risks? (1) Shop organic if available and affordable; (2) Always wash fresh fruit and vegetables thoroughly to remove organochloride pesticides; (3) Consider using a weak natural detergent to ensure you get fruits and vegetables completely clean (e.g., products such as fit, ECOS, etc.); (4) Avoid plastic bottles, cups, and other food containers unless they are certified BPE-free.

How do you treat thyroid cancer?

When thyroid cancer has been diagnosed, the first thing your Endocrinologist will do is refer you to a neck and thyroid surgeon for thyroid removal (thyroidectomy).

This is typically an Ear, Nose, and Throat (ENT) surgeon who has done additional training and has extensive experience in doing surgery in the front compartment of the neck, which contains the thyroid gland, parathyroid glands (discussed in other areas on our site), and lymph nodes that communicate with the thyroid.

Controversies exist regarding whether to take out one lobe or both lobes of the thyroid (lobectomy vs. total thyroidectomy surgery) and whether to treat people who had total thyroidectomy with radioactive iodine (131I).

The intent of treating with radioactive iodine is to destroy and “mop-up” any remaining thyroid tissue, loose thyroid cells, or lymph nodes with microscopic amounts of thyroid cancer in them that the surgeon may not have been able to remove at the time of surgery.

It is important to discuss your specific case with your Endocrinologist and neck/thyroid surgeon to decide what course of treatment best fits your case.

Total thyroidectomy or lobectomy for thyroid cancer?

Even though thyroid cancer is usually present on just one side of the thyroid gland, a total thyroidectomy is frequently recommended, since if you have cancer on one side, there is about a 30% chance you will develop it on the other side at a later point in time. Hence, if an ultrasound-guided biopsy shows that you have cancer before a surgery, then typically you will get a total thyroidectomy to be safe.

Having said that, current medical opinion has been slowly shifting toward doing fewer total thyroidectomies and more half-thyroidectomy (1 lobe surgeries where only half the thyroid is removed) when a known cancer nodule is under 4 cm in size and lacks other worrisome features, and there are no signs of potential cancer in the other lobe.

Other names for a half-thyroidectomy are lobectomy or hemi-thyroidectomy. Thyroidectomy surgeries can be associated with a great deal of bleeding since the thyroid is a very vascular organ (lots of blood flows through it), and so removing the entire lobe (or both lobes) encapsulated and intact, rather than trying to cut a nodule out of a lobe, is always preferred by surgeons, since it is very difficult to repair the lobe and prevent it from bleeding after cutting out a nodule.

Nodule removal surgeries are almost never done anymore. In summary, whether to get both lobes or just one lobe removed is increasingly controversial and so you should discuss the risks/benefits of each approach with your Endocrinologist.

Should I have radioactive iodine treatment for thyroid cancer?

Treatment with radioactive iodine after total thyroidectomy has the advantage of removing any thyroid tissue that may have been left in the thyroid bed by the surgeon. Even the best surgeon cannot remove every small piece of thyroid tissue, or every cell floating around inside your neck or in your lymph nodes. Radioactive iodine (131I) is taken up primarily by thyroid cells and kills them off over a period of a few days to weeks after treatment.

Radioactive iodine is meant to target and permanently destroy most, if not all, of the remaining thyroid tissue/cells in the body. When there is little or no thyroid tissue left, blood levels of the protein thyroglobulin are usually extremely low, often undetectable, making it possible to check blood levels of thyroglobulin regularly as a way to monitor your for return of thyroid cancer in the neck or elsewhere.

Since measuring thyroglobulin in blood is such a sensitive method, rising thyroglobulin levels can often alert your Endocrinologist that thyroid cancer is returning long before it can be detected by neck ultrasound or other approaches. Recent medical opinion, however, leans toward the notion that radioactive iodine is being used too often.

Specifically, there are some risks for chronic injury to salivary and tear glands (among the few other tissues that take up radioactive iodine), the potential for radioactive iodine to cause “secondary” (new) cancers in other tissues, and of course, the overall cost and effort spent on the treatment.

Having said that, several large studies have indicated that people who undergo treatment with radioactive iodine after thyroidectomy report greater ease of managing their condition, better overall peace of mind, and improved quality of life compared with those who opt out of radioactive iodine. So, the question of whether to treat with radioactive iodine also remains controversial for many thyroid cancer cases and should be discussed for your specific situation with your Endocrinology.

Should I take extra thyroid medicine to suppress my TSH level if I have had thyroid cancer?

After a total thyroidectomy for thyroid cancer, everyone requires thyroid hormone replacement (since they now have no thyroid). Some people may additionally benefit from taking a bit of extra thyroid hormone to “suppress” their TSH levels, since TSH is a growth factor for thyroid cancer and lowering it can help reduce the chance that thyroid cancer will return. Recall: TSH goes opposite the direction of how much thyroid hormone is in your blood, and so giving more thyroid hormone for replacement will lower TSH to the point where it is below normal (or even undetectable if too much thyroid hormone is given). However, the decision to take extra thyroid hormone medicine must be made carefully, since some people may develop heart or bone problems if they are getting too much.

If your thyroid cancer was relatively low-risk to begin with (less than 4 cm in size, involved only one lobe of the gland and only one area within that lobe, did not invade tissues around it, and did not invade your neck lymph nodes), then your Endocrinologist may suggest you keep your TSH in the low normal range (0.5 to 2.0 mcIU/mL) and observe on an annual basis by measuring your blood levels of the thyroid tumor marker, thyroglobulin, and checking your neck by ultrasound. People who underwent a lobectomy only for thyroid cancer (i.e., a hemi-/half-thyroid surgery), also typically fall into the same category, and have a goal TSH of 0.5 to 2 mcIU/mL; some people who still have half a thyroid will not require thyroid hormone treatment to keep their TSH in this low-normal range.

If your thyroid cancer showed some higher risk features at the time of diagnosis and surgery, your Endocrinologist may recommend some extra thyroid hormone to keep your TSH in a slightly suppressed range (0.1 to 0.4 mcIU/mL where 0.5 mcIU is the low-end of normal). If over time there are signs based on blood testing or ultrasound that your thyroid cancer is returning, your Endocrinologist will usually increase your thyroid hormone dose a bit to get your TSH level to less than 0.1 mcIU/mL and then start monitoring more intensely to look for recurrent thyroid cancer and treat it if found.

People with aggressive, high risk thyroid cancer will usually be given enough thyroid hormone to keep their TSH less than 0.1 ng/mL from the start, and levels will be kept there indefinitely while they are monitored closely. If there are signs of recurrent cancer, options may include treating a second time with radioactive iodine, having a neck surgeon explore and remove more lymph nodes (neck lymph node dissection), or a combination of approaches. In addition, imaging to look for thyroid cancer that might have spread outside the neck is also usually undertaken. People who undergo TSH suppression to levels less than 0.1 mcIU/mL should be monitored for cardiac symptoms, and depending on age and other risk factors, it may be a good idea for them to have bone density testing.

Frequently Asked Thyroid Questions

Is a thyroid problem serious?

As with anything, the answer to this depends on the specific problem. Thyroid problems can range from a small nodule that requires no treatment to full-blown invasive thyroid cancer. They can range from out of control, raging Graves disease (severely overactive thyroid gland) to mild Hashimoto’s disease which has few or no symptoms at all. The most common issues associated with the thyroid is an abnormal production of thyroid hormones, either hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism. Although these conditions can cause unpleasant symptoms, they are usually not immediately life-threatening and can be managed through diagnosis and standard medical treatments.

How does thyroid affect the body?

The thyroid controls the rate of metabolism, specifically how quickly and efficiently your body utilizes nutrients to make energy. It regulates body temperature, heart rate, brain function, mood and concentration, the speed at which electrical signals travel through nerves, muscle strength, hair, skin, and nails.

What are the symptoms of thyroid problems in females?

Overall, women are more likely (4 to 1) than men to develop thyroid problems in their lifetime. In addition to the most common symptoms from thyroid issues (feeling hot/cold, weight changes, mood changes, difficulty concentrating or sleeping, fast/slow heart rate, overactive/underactive nerve conduction, muscle weakness, aches, and pains), women may discover that they are having problems with their menstrual period, have problems getting pregnant, and problems during their pregnancy

What are the early warning signs of thyroid problems?

Some early symptoms of thyroid problems include high heart rate, heart skipping beats, excessive tiredness, weight gain/loss, anxiety/depression, feeling hot/cold all the time, muscle weakness/aches/pains, tingling in fingertips and feet, changes in menstrual period or sex drive, dry or oily skin, thin or falling-out hair, brittle/cracking nails, redness/irritation/poking-out of eyes, swallowing problems, pain in the front of the neck near the base of the neck, voice hoarseness, or a bump or swelling in the neck below the Adam’s apple.

What is the main cause of thyroid problems?

There are a few reasons that you may have developed issues with your thyroid. Some of these include autoimmune disorders, nodules on the thyroid, including thyroid cancer, genetics, and pituitary problems. In the United States, lack of iodine is NOT a cause of thyroid problems.

Can Stress Affect Your Thyroid?

Stress will not cause any thyroid problems, but it may worsen existing symptoms.

How can I check my thyroid at home?

You can check your thyroid at home by performing a small physical exam. Simply feel the base of your neck for any nodules or swelling. The thyroid sits very low in the neck, at least half an inch below the Adam’s apple.

Then, try swallowing while looking at your neck with a hand mirror. See if you notice any abnormalities like a lump or asymmetry (one side larger than the other) when swallowing. Because swallowing pushes the thyroid gland forward and forces it to move up and then down, these things are often more visible when you take a gulp.

Both when you feel your gland and when you observe your gland with swallowing, you are primarily looking for lumps/swelling or irregular shape/asymmetry. If you see anything suspicious, make an appointment to see an Endocrinologist who specializes in thyroid care.

What are the complications of thyroid problems? /What happens if a thyroid problem goes untreated?

If left untreated, a thyroid problem can cause serious health issues. Over time you may develop heart problems, lose bone mass, experience weight gain/loss, develop anxiety/depression, or become infertile. Most of these problems occur over time and are not medical emergencies. The key is diagnosis and treatment before they become a problem. Even so, severe hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid gland) or severe hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid gland) can be serious enough to be life-threatening and cause hospitalization.

How can I fix my thyroid naturally?

There are several ways to help combat the symptoms from a problem with your thyroid. In general, AVOID thyroid supplements that contain iodine since these can make thyroid problems much worse. Iodine is present as an additive in almost all our salt in the United States, such that iodine deficiency generally is not a problem.

In contrast taking iodine can suppress the thyroid gland causing hypothyroidism, or in some cases have the opposite effect to induce overactivity of the gland. Iodine can also accelerate the growth of some thyroid nodules and activate thyroid autoimmunity.

So, in summary, avoid iodine. Selenium is an easy to find supplement that may help with some symptoms of underactive thyroid. However, most issues require medical treatment and you should start by seeing and Endocrinologist who specializes in thyroid care.

What is the best treatment for thyroid problems?

The best treatment for thyroid problems depends entirely on what the problem is, in some cases you may have an underactive thyroid and need medications that replace your natural thyroid hormones.

In other cases, you may have an overactive thyroid and need medications that slow down your thyroid activity, or treatment with radioactive iodine to destroy your thyroid gland permanently, or surgery to remove your thyroid gland permanently.

Radioactive iodine or thyroid surgery are usually needed for treating thyroid cancer and may also be necessary for treating thyroid nodules. Of course, once your thyroid is destroyed or removed, you will then need medications that replace your thyroid hormones.

Can thyroid problems be cured?

All thyroid issues can be treated, meaning with the right care for your thyroid, you can make sure your thyroid hormone balance returns to normal. In many case, however, the underlying problem cannot be cured, with a few exceptions such as thyroid surgery to remove an enlarged or overactive thyroid gland.

But even that sort of “cure” means you will need to be treated with medication typically for life. So, while a thyroid problem “cure” is usually not possible, a permanent fix for thyroid problems usually is.

What is included in a full thyroid panel?

A “full” thyroid panel should include TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone) and the “free” thyroid hormone levels, Free T4 and Free T3. We do not recommend routine measurement of total thyroid hormones (total T4 or total T3), since these often do not reflect your thyroid hormone balance accurately. In addition, the common practice of ordering “Reverse T3” is a useless practice for 99% of the population.

Despite obsessive internet conjecture, levels of Reverse T3 do not predict or explain any thyroid problems, and is only useful for diagnosing individuals who have an exceedingly rare thyroid hormone resistance condition known as Thyroid Hormone Cell Transport Defect (THCTD), related to a mutation in the gene MCT8, monocarboxylate transporter 8.

Why would a doctor order a thyroid ultrasound?

An Endocrinologist may want to perform a thyroid ultrasound for a couple of reasons. They may perform an ultrasound if they feel a lump on your neck when examining it or if you have symptoms with swallowing, pain in the front of your neck, or unexplained voice hoarseness; or if you were found to have abnormal test results from a thyroid function test.

What are they looking for in a thyroid ultrasound?

An ultrasound can help a doctor determine if biopsy is required to determine the effect of a thyroid nodule. It may also give some information about whether a person has an overactive or an underactive thyroid or if there are signs of thyroid autoimmunity, such as Hashimoto’s disease.

Can a thyroid ultrasound detect cancer?

An ultrasound can show the size of a thyroid nodule, whether the nodule is solid or contains liquid, or contains features that are suggestive of cancer (such as certain types of calcium deposits, a large amount of blood vessels inside it, or irregular “blurry” margins”. However, the ultrasound primarily leads your Endocrinologist to decide whether or not to perform an ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy which provides the key information about whether cancer is present.

What is an abnormal thyroid ultrasound?

An abnormal ultrasound may find a growth on or around the thyroid gland, an enlarged or irregular thyroid gland, called a goiter, or lymph nodes in the area of the thyroid.

What is Hashimoto’s disease?

While it sounds scary and exotic, Hashimoto’s disease is more common in the population than being left-handed. Hashimoto's disease (also known as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis) is an autoimmune disorder that can cause underactive thyroid, also known as “hypothyroidism”. Hashimoto’s disease is caused by a slow but relentless attack of T cells against the thyroid gland. A byproduct of this attack is the production of thyroid antibodies that can be detected in blood. Hashimoto’s disease may be the single most common autoimmune disease: fully 1 out 6 women develop thyroid antibodies in their lifetimes.

Hashimoto’s is also the primary cause of hypothyroidism in women. 95% of women with hypothyroidism have Hashimoto’s disease, whether or not they know it. This is such a reliable finding, that most Endocrinologists do not bother measuring thyroid antibodies in a women with hypothyroidism, since the presence of antibodies or their levels do not generally influence diagnosis or predict symptoms or severity of hypothyroidism. In addition, it is generally not helpful to repeatedly measure antibody levels since the levels do not correlate with symptoms or outcomes.

How serious is Hashimoto's disease?

Hashimoto’s disease is not a very serious disease, except that it can and often does lead to hypothyroidism. Untreated hypothyroidism, on the other hand, can cause a host of other health problems. In people with Hashimoto’s disease who have normal thyroid function, the autoimmune condition and the antibodies associated with Hashimoto’s produce few or no symptoms, with the exception that some people seem to experience a variety of hair, skin, and nail problems, even when their thyroid hormone levels are in very healthy ranges.

The cause of this connection between Hashimoto’s disease and hair/skin/nail issues remains unknown. Despite the lack of major medical issues other than hypothyroidism associated with Hashimoto’s disease, there is a great deal of misinformation and overblown claims about Hashimoto’s disease on the internet. While it is great to educate yourself by browsing the internet, it is also important to become a savvy consumer of internet medical information.

Most websites that portray Hashimoto’s disease as a serious or dangerous condition are trying to sell you something—typically a supplement, a diet, a book, or a membership, or they are just trying to get you spend time clicking through their web pages in order to make more money from web advertising (yes, that is how sites like those make money). We recommend being very skeptical of any claims on the internet that any condition is the end-all, be-all cause of all your problems in life. Learn to be a savvy consumer of medical information on the internet!

What triggers Hashimoto's disease?

Hashimoto’s disease is caused by a malfunction of the immune system that causes T lymphocytes (T cells) to attack your thyroid instead of protecting it. In this process, thyroid antibodies are also generated by B lymphocytes (B cells). Interestingly, pregnancy may be one the more common triggers for this in women.

The connection between pregnancy and thyroid autoimmunity is not well understood but might relate to the release of fetal (baby’s) cells into the maternal (mom’s) circulation around the time of delivery. The fetal cells are only half-related to mom by genetics, and so her immune system may recognize them as “foreign” and get triggered.

For unknown reasons this results in activation of immune cells against the thyroid in particular. One factor that has been shown to NOT trigger Hashimoto’s disease in large, well-controlled studies is gluten. Nope: gluten in the diet does not seem to cause Hashimoto’s disease, despite the many firm claims about this on the internet. And vice-versa, Hashimoto’s disease does NOT trigger Celiac disease (autoimmune gluten intolerance).

However, there is a real connection between the two conditions–the same immune system tendency to develop trigger one of these conditions also seems to make it more likely to trigger the other, and this same immune system tendency also extends to more serious conditions like Type 1 diabetes and Addison’s disease. So, while there is a connection between Hashimoto’s disease and Celiac disease, it is not a “causal” one, but rather that they both “arise from common soil”.

Most websites that insist Hashimoto’s causes Celiac disease or that gluten in the diet causes Hashimoto’s disease are just trying to sell you something—typically a supplement, a diet, a book, or a membership, or they are just trying to get you spend time clicking through their web pages in order to make more money from web advertising (yes, that is how sites like those make money).

We recommend being very skeptical of any claims on the internet that any one condition is the end-all, be-all cause of all your problems in life. Learn to be a savvy consumer of medical information on the internet!

What is Hyperthyroidism?

Hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid) occurs when your thyroid gland produces too much of the hormones thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). Hyperthyroidism can also occur from taking too much thyroid hormone replacement medication.

How will I feel if I have hyperthyroidism?

At first, hyperthyroidism may make you feel hot and sweaty, jittery, and develop a tremor in your hands. Over time, you may notice that your heart is beating fast, that you feel anxious, you have insomnia, or you are having an unusual number of bowel movements. You may also feel like you just don't have as much energy as usual.

What is Hypothyroidism?

Hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid) occurs when your thyroid gland does not make enough thyroid hormone to keep the body running normally. People are considered hypothyroid if they have too little thyroid hormone (levothyroxine (T4) and liothyronine (T3) in the blood.

What causes hypothyroidism?

Hypothyroidism results when the thyroid gland fails to produce enough hormones. Hypothyroidism may be due to a number of factors, including an Autoimmune disease. The most common cause of hypothyroidism is an autoimmune disorder known as Hashimoto's thyroiditis.

How can you prevent thyroid problems?

There is no definitive way of preventing thyroid disease. However, you can lower your risk of complications by quitting smoking, doing routine checks, and asking for a thyroid cover when receiving an X-Ray.

What foods are bad for the thyroid?

There are almost no foods that are bad for the thyroid, with the possible exception of foods with high amounts of iodine. In some cases, these foods can injure the thyroid gland if eaten in excess. So, avoid eating tons of seaweed (nori) or taking iodine supplements or natural “thyroid support” formulas that contain lots of iodine. In places around the globe where iodine is not present in the diet, people can and do develop iodine deficiency which leads to underactive thyroid problems and goiters.

However, in the United States, our salt is iodinated, and even non-iodinated salt contains iodine, and we eat a lot of salt in this country. When your iodine levels are already in healthy or even high ranges and you then add more iodine to your diet through certain foods or supplements, you can actually have the unintended effect of causing hypothyroidism and inducing thyroid nodules or thyroid autoimmunity.

It is sort of a “U-shaped” curve: on one end, too little iodine causes those problems, and on the other end, too much iodine also causes those problems—so you want to be in the middle on iodine consumption. One dietary factor that has been shown to NOT trigger Hashimoto’s disease in large, well-controlled studies is gluten.

Nope: gluten in the diet does not seem to cause Hashimoto’s disease, despite the many firm claims about this on the internet. And vice-versa, Hashimoto’s disease does NOT trigger Celiac disease (autoimmune gluten intolerance).

However, there is a real connection between the two conditions–the same immune system tendency to develop trigger one of these conditions also seems to make it more likely to trigger the other, and this same immune system tendency also extends to more serious conditions like Type 1 diabetes and Addison’s disease.

So, while there is a connection between Hashimoto’s disease and Celiac disease, it is not a “causal” one, but rather that they both “arise from common soil”. Most websites that insist Hashimoto’s causes Celiac disease or that gluten in the diet causes Hashimoto’s disease are just trying to sell you something—typically a supplement, a diet, a book, or a membership, or they are just trying to get you spend time clicking through their web pages in order to make more money from web advertising (yes, that is how sites like those make money).

We recommend being very skeptical of any claims on the internet that any one condition is the end-all, be-all cause of all your problems in life. Learn to be a savvy consumer of medical information on the internet!

What should I do next?

Schedule an appointment with Diabetes and Endocrine Specialists right away. You can do that without a referral, but we are also happy to receive a referral from your regular doctor. Once we understand your problems, we can run some tests, make a diagnosis, provide you with education, and develop a management plan that works for you.

Hyperthyroidism Resources

Hypothyroidism Resources

Hashimotos Resources